Alaska and the Mail Dog Trail

Dad’s other sister Aina, and her husband Gus, had gone to Flat City, Alaska, from Butte, Montana, when rich placer gold deposits were discovered in 1913. Dad’s brother Oscar and his wife and daughter also went from Butte. But a few years later they moved to Detroit, after first trying farming in New York State.

Oscar began making trips to Flat City where he worked as shoreman on a gold dredge. His wife and daughter stayed in Detroit. Oscar went each spring to Nenana, Alaska, where he got off the train, and with a packsack on his back, walked about four hundred miles to Flat, following the winter mail dog team trail. Each fall, when the dredge had to be shut down due to freezeup, he walked back to Nenana and returned to Detroit for the winter.

In January 1929, he came to visit us. When he asked me if I would like to go to Alaska with him, I happily answered, “Yes!” I sent a telegram to Alex Mathieson, owner of the gold dredge, asking for a job as oiler on his dredge. An answer came back saying a job was waiting.

The latter part of February I went to Detroit. During my stay at Oscar’s we saw the movie, “The Trail of 98,” which showed people by the hundreds going up Chilkoot Pass on the gold stampede to Dawson. It looked so rough that I began walking to get in shape for the long hike.

We left Detroit the end of February. On the train a big, husky young man sat across from us. He told us his name was Frank Dorbandt, and he was an airplane pilot for Anchorage Air Transport, on his way north.

After spending a few days sightseeing around Seattle, we boarded the steamship Alaska for the trip to Seward. The fare was eighty-seven dollars each, which included meals and a stateroom with two berths. The ship sailed up the Inside Passage all the way except through the Gulf of Alaska, where it went through open ocean.

The trip to Seward took seven days because of the numerous stops at coastal towns and fish canneries to take on fish and unload freight. I was told that the Gulf got extremely rough at times but our passage was smooth. We walked every day around the deck of the ship to toughen up, and went ashore in most of the towns. I saw huge whales spouting in the Gulf, a most amazing sight to me.

The train was waiting for us at Seward so we went straight from the ship to the train. Before we reached Anchorage, Frank Dorbandt tried to talk us into getting off there and letting him fly us to Flat City. The airplane fare was three hundred and fifty dollars per person. We refused because Oscar said we had plenty of time, that meals and lodging would be only sixty‑five dollars each over the trail.

The train stopped at Curry for the night where all the passengers slept at the Government owned Curry Hotel. The next day the train went to Fairbanks. Oscar and I got off at Nenana to stay overnight at the small two story Cooney Hotel.

In the morning it was thirty below zero outside but with our parkas on, and packsacks on our backs, we headed west. The mail dog trail, hard and well‑packed, was built up about three feet but the sides were soft and fluffy snow.

Government maintained and manned roadhouses made of logs were spaced approximately twenty-five miles apart along the mail dog trail. The charge was four dollars and fifty cents a night, which included supper and breakfast; also a bunk and blankets. A few relief cabins did not have a caretaker. We bought food from the previous roadhouse for our overnight stops at these cabins, and saw to it that we left wood and kindling for the next traveler, as was the custom.

Our first day out of Nenana we met Bill Burke coming with his mail team of twenty six dogs. We stepped off the trail to let him pass, but the dogs began barking and seemed determined to get at us. We waded as fast as we could to get farther away while Bill kept cracking his long whip to get them by. That time I was scared‑‑those dogs looked vicious.

At the first relief cabin, nineteen miles from Nenana, we built a fire in the Yukon stove, ate some of the food that we had brought, cut wood for the next traveler, then curled up on the wide bunk made of spruce poles and covered with spruce boughs. We had only our parkas for quilts but big chunks of wood in the stove kept the cabin warm all night. The next morning the muscles on our legs were so sore that we had trouble walking, but after a few miles the pain ceased.

We spent our second night at the east Fork Road House, third at Knight’s, fourth at Roosevelt, fifth at Lake Minchumina, sixth at the Lake Minchumina relief cabin. That was a rough day because we were on the open lake most of the day with a howling wind and snow storm facing us the whole distance of twenty-six miles. The relief cabin sitting there among big trees on the bank of the lake‑‑boy, were we glad to see that.

The next day about noon my eyes started paining, feeling as if they were full of sand. I had not worn my sun glasses enough so was suffering snow blindness. That night after we got to Lone Star Roadhouse the caretaker suggested that I cover my eyes with a cold wet towel. It did relieve the pain somewhat, but each day after a few miles they began to pain me again, although I constantly wore my black glasses.

During the night it had snowed about a foot and was still snowing. Walking was tough for we carried no snow shoes. Luck was with us though, because before noon we met Charles O’Halloran with his mail team of twenty four dogs. Bill Burke went half way from Nenana to Flat City and return, and O’Halloran had the run from Flat City to the half way point and return.

It quit snowing and we had a good hard trail to the Tolida Indian Village Roadhouse, run by one of the Indian families. Not a soul was at the village. The roadhouse was unlocked so we went in, stoking up the fire, fixing ourselves a good hot meal from their supplies.

Just before dark we hard the Indians coming home with their dog teams, all making a lot of noise; dogs barking and people laughing and shouting. The whole area seemed full of dog teams and sleds. The Indians were dressed in their fancy parkas, many of which had the most beautiful fur work, with intricate beadwork, insets of different furs, decorations of animal tails, claws and teeth. They had all been to a neighboring village potlatch, a gift‑giving celebration. For a greenhorn country boy, it was quite a sight.

The next morning the natives who operated the roadhouse made a breakfast of hot oatmeal, ham and eggs, and hotcakes made of sourdough. They had the usual cooked prunes, a dish that I looked forward to morning and night. The custom at all the roadhouses was to have cooked prunes and other dried cooked fruits on the table all the time. We could help ourselves any time we wished. Each morning we rolled up a few of the sourdough hotcakes, sprinkled with sugar, and took them along for our noonday meal.

About noon we came to an Indian cabin. The man came out to invite us in for a cup of coffee and a moose meat steak. His wife had been bedridden for years, paralyzed from the waist down. Their young daughter fried the steaks and made the coffee, the strongest coffee I ever had, with no milk or sugar. Oscar ate all of his steak but I could not hack it because it was scattered with moose hairs and was half raw. I told them I wasn’t hungry. We each gave them two dollars for their trouble and food.

About a quarter of a mile from their cabin we came to a V in the trail. Both directions were equally well‑packed so we were not sure which way to go. Oscar thought it was the right hand trail, so we followed that for what we felt was over a mile. No mile marker appeared so we went back to the Indian cabin to ask the way. He said the left hand one was his wood hauling trail and we should go to the right. We were angry because he had not put some kind of a marker there. Returning to the spot where we turned back, there, around a bend in the trail, was the mile marker; a few feet more and we would have seen it. This day was the longest run of all for it was thirty nine miles counting the turnback to the Indian cabin.

Rhone River Roadhouse was next, then Medfra, a native village that had a post office and a small store. Big River came before the much larger village of McGrath. McGrath was as far up the Kuskokwim River as the river freighting barges could navigate. It had an airplane landing field, a large Northern Commercial Company general store and another smaller store. We could have cut off about fifty miles if there had been a trail broken to Flat, but the mail trail went via Takotna and Ophir.

The village of Takotna was smaller than McGrath but it did have a landing field and a store. The next day on our way from Takotna we stopped at Victor and Amelia Hill’s house about six miles from Ophir. They were good friends of Oscar’s. They made their living by mining gold with only water pressure and wheelbarrows.

Mrs. Hill fixed us a lunch of moose meat roast and vegetables from their root cellar. As I was still suffering with snow blindness, Vick told me to see Eric Hard when we got to Ophir. He was an elderly man, one of those jack‑of‑all‑trades people, who learn a lot through experience and reading. He was the village dentist. That is, he pulled people’s teeth with an ordinary pair of pliers and no anesthetic. He was the blacksmith and barber too. He put a drop of nitrate of silver in each of my eyes and I went to bed. The next morning I noticed brown liquid had run out of my nose, and my troubles were over.

Birches relief cabin was next and then the Shermeyer Roadhouse. These roadhouses may not be listed in correct order. I cannot remember that far back.

On the seventeenth day we came to Iditarod. In 1912 when gold was discovered on Flat Creek eight miles away, the town of Iditarod was formed because it was as far up the Iditarod River as the river barges were able to go.

Over three thousand people had lived there for several years, with stores, bars, cards and gambling halls. A short distance from town was the line of prostitutes’ cabins. Several of the old buildings were still standing but were sunken and leaning from thawing and heaving of the permafrost on which they were built. A small railroad called the Tramway, with rails made from wooden two by fours, had run from Iditarod to Flat Creek. It had a few flat cars equipped with seats, on which the miners rode to and from work. A gasoline engine was used for power.

When Flat city came into being, the government‑operated Alaska Road Commission built a gravel road from Iditarod to Flat, and the Tramway was abandoned.

Iditarod became just a riverboat landing. A few people still lived there, including Tootsie, a black woman, who had come to Dawson during the big gold rush in 1898 and finally ended up in Iditarod, where she operated a small cafe. We stopped to visit with her and had coffee and apple pie made from canned apples. She, too, later moved to Flat City, continuing with her cafe until about 1968; then moved to Fairbanks to the Pioneer’s Home, where she died a few years later.

Tootsie often said, “I was the first white woman who ever went to Dawson!”

In Iditarod a big warm storage building had been built, into which all the perishables were unloaded each time the river boats came. A caretaker lived in this building to keep the wood fires going in winter in the big stoves, made out of two one‑hundred‑gallon oil drums riveted end to end. They were long enough so four foot chunks of wood could be shoved into them. In summer the caretaker helped move the supplies into storage when boats came in.

Many cases of eggs were stored through the long winters and became pretty rancid. In 1929 when fresh eggs were brought in by airplane, one of the old timers told me that he didn’t like those airplane eggs‑‑”There’s no taste to them. They taste so flat.” After visiting the caretaker for awhile, Oscar and I headed for Flat.

Gus had a contract with the store owners and miners to haul their goods. He had four big black horses, each weighing a ton. We had walked only a couple of miles when we met him coming with two sets of sleds hooked in tandem. The team on the tongue was called the heelers, the pair on the end of the tongue were the leaders.

Gus insisted that we ride back to Iditarod with him but we refused because we wanted to have a much needed bath at the sauna operated by the Miscovich family in Flat.

Oscar mentioned again that just as soon as we get to Flat we will go and see the black bear. I was pretty anxious to see it, never having seen one, and supposing they had one in captivity.

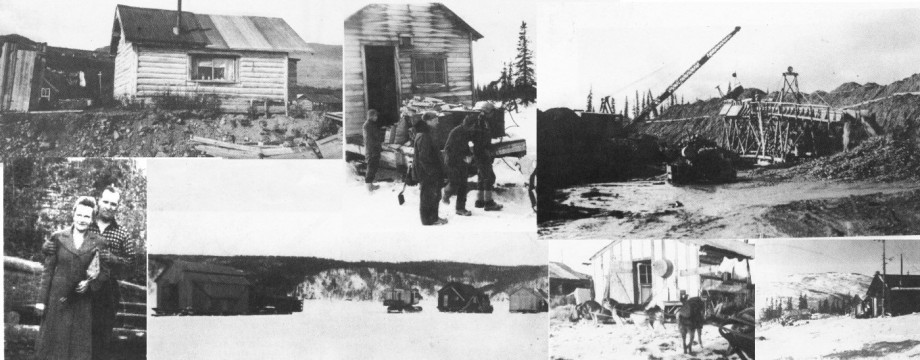

Just before we got to Aunt Aina’s we walked past the school house, a fairly large building with the teacher’s quarters in the back. I saw the two general stores, large old log buildings which had leaned and sunk into the soft summer tundra. A restaurant and a post office made up the rest of the business establishments. One and two‑room cabins were scattered here and there and some were partly sunk into the ground. Each cabin had an outhouse in the back. In the middle of town was the Moose Hall, in which meetings, and occasional dances with a phonograph for music, were held.

I noticed about ten cabins a short distance below town with a board sidewalk connecting them. Oscar told me they belonged to the prostitutes or line girls as they were called. The rest of the town had to suffer narrow muddy foot paths.

Soon several of the miner’s wives arrived at Aina’s. After coffee and cake, I said, “Oscar, let’s go see the black bear now.”

The women all gave me strange looks. After they left Aina started bawling me out for embarrassing her. She told me “Black Bear” was a nickname given to one of the line girls. Then she turned on Oscar who couldn’t stop laughing at the hilarious ending to his joke.

The line girls all had nicknames. There were the Oregon Mare, Panama Hattie, Finn Annie, Frisco Kate, and many others. We never did hear their real names.

One of the old timers told me that a few years ago one of the line girls fell for one man very hard. She heard he was seeing one of the other girls too. She got jealous and fired a pistol shot intending to put him out of business, but aimed a little too low and hit him in the leg. I guess he had had enough of women, because he left town.

Oscar and I went to the store. We met John Ogriz there, who said he had a twelve by fourteen log cabin that he would sell me for one hundred and fifty dollars. After buying it, I moved right in. It had a small bed, a Yukon stove, a homemade table and a couple of chairs, I bought a Wood’s eiderdown sleeping bag, a pillow and sheets, and asked Gus to bring me a few cords of wood. I did not need any groceries because I began eating three meals a day at Henry Durand’s restaurant. He charged a dollar a meal. Oscar had a room in the end of Gus’s garage and did his own cooking. During the winter months Gus and Aina used to live at their wood cutting camp several miles from Flat. The place there was a big building with a wall between them and the horses. The wood cutters stayed in a separate log building.

Gus paid them fourteen dollars a cord. Aina did the cooking for the men while Gus made a trip to Flat every day with his two teams of horses, pulling big loads of wood on two sets of sleds.

After a few winters they quit going to live at the wood camp, with only the men staying there. Gus later ordered a new Cletrac track‑type tractor from Seattle with which he hauled wood, but he soon ruined the engine by running it too low on oil. He later ordered two new Ford flatbed trucks and did all his freight hauling from Iditarod with them.

Large amounts of wood were needed to heat all the building and homes, and hundreds of cords were used by the owners of the two gold dredges to fire the big steam boilers. These were used each spring to provide steam for pipes, called steam points, driven into the ground a few inches at a time in front of the dredges, to thaw the permafrost so digging could start. Steam was also used each fall to keep things thawed on the dredges so digging could continue as late as possible.

As soon as water began to run and after the dredge started, a gang of men drove hundreds of pipes about ten feet apart into the ground. Cold water under pressure through a pipeline from a ditch up on the hillside was forced down through. Several men, moving stepladders from pipe to pipe, gave each pipe a couple of taps with a heavy short‑handled hammer and a twist with a handle attached to the pipe, then moved on to the next one. This method was called “cold‑water thawing.”

I went to work in a few days, digging a trench all the way around a big warehouse, which was to be jacked up and moved because rich gold deposits were in the ground under it. It had sunk about a foot into the soft boggy ground during summers, but now the muck was frozen as hard as cement. Alex Mathieson, my boss, popped around the corner every little while to see if I was loafing, I suppose. I was determined to build a good reputation for myself so worked hard and steadily without stopping.

The bucketline that did the digging on the dredge had seventy buckets. Each bucket had a manganese steel cutting lip attached to the bucket with twelve three‑quarter inch rivets. My second job was to beat with a heavy sledge hammer on a rivet‑cutting chisel with a wooden handle that was held by one of the men. After cutting off the rivet I beat on a wooden‑handled punch to punch out the rivets. I had to swing the sledge again to flatten down the hot rivets which held the new lips in place. I swung the sledge for ten hours a day and no one spelled me off. But after the long walk I was in such good shape that I was not very tired evenings.

About the middle of May we finished overhauling the dredge. The big diesel engine started the wheels, gears, belts and bucketline turning for twenty four hours a day with a stop each day for ten minutes to allow us oilers to pump heavy waterproof grease into the bearing hubs of the lower tumbler, which was the big lug wheel on the bottom of the digging ladder around which the bucketline revolved. The oiling job was easy. All I had to do was make a round every four hours and give each grease cup a little turn. Once each day I heated heavy black gear grease on the forge and poured some on all the open gear teeth. There were all kinds of gears, shafts, belts and pulleys.

Each time when the big trommel screen made a metallic clanking sound, I knew that the bucketline had brought up a hammer, pick, axe, wrench or something else people had lost. I would run down or up to the center deck to catch whatever it was as it came out onto the conveyer belt. I cleaned it on the emery wheel wire brush, made new handles and painted them, thus keeping the dredge well supplied with tools.

Salmon came up Otter Creek by the hundreds on their way to spawn. As the creek ran through the dredge pond, the bucketline brought up salmon, dumping them into the trommel screen. When they came out onto the conveyer belt they were dead and pretty well mashed up.

One bearing had a grease cup so high that I had to reach up to get hold of it. The endplay washer next to the bearing was held to the shaft with a long square head set screw. Once when I reached up to turn the grease cup the screw caught the sleeve of my coveralls and began to wind my arm around the shaft. I gave a mighty jerk and tore my sleeve but saved my arm. It was a slow‑turning shaft, thank goodness.

My wages were ten dollars a day so I got a check at the end of each month for three hundred ten dollars. I cashed the checks at the Miner’s . and Merchant’s Bank, and was paid in five, ten and twenty dollar gold pieces. One side of my trousers was quite heavily loaded as I walked to the restaurant to pay the board bill and to the post office, where each month I bought a money order and mailed most of my earnings to mother and dad. Farming was very bad during those depression years and they could not make ends meet.