Day In, Day Out

After five trips we had all the supplies moved to Moore Creek. The cook, Lena Toner, rode to camp on the last trip. She had come from California and was waiting in Flat.

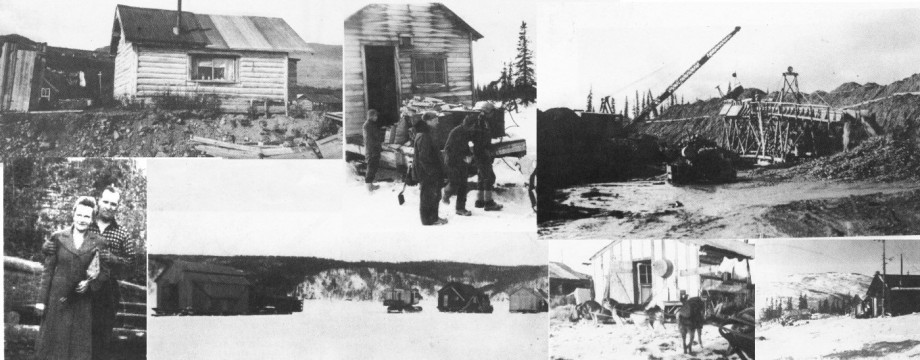

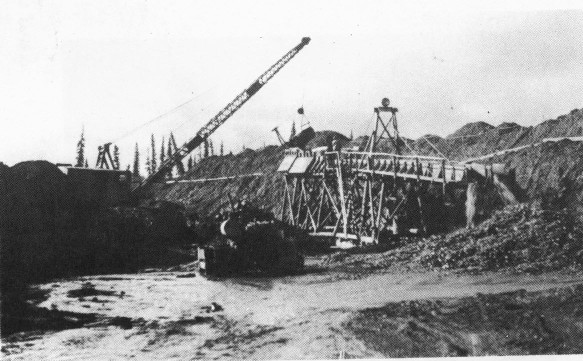

We built a trestle sixty feet long on big wooden skids. The upper end was twenty feet high, sloping down to ten feet on the lower end. On the upper end we mounted a wide high-sided dumpbox, and from there down, boxes thirty-four inches wide with riffles in the bottom to catch the gold. A pipeline from our ditch up on the hillside provided water under j pressure to wash the gravel, floating it down through the boxes as the dragline dumped it into the dumpbox.

Moore Creek Dragline (1937) “Our dragline dumping gold bearing gravel into the dump box of our trestle at Moore Creek. The old 60 bulldozer pushed away the tailings. "

With the old 60 bulldozer we kept pushing away the washed gravel (tailings) as it came out the lower end of the boxes. Mining started on June ninth and fifteen days later was cleanup day. This pleased us no end j because it was more than we took out the whole previous summer.

It looked so good that we had Eugene send a wire for a new D-8 bulldozer from Seattle. He operated our radio transmitter and receiver so we could order things, and ran the dragline on the day shift. His radio schedule was at seven o’clock each evening with Frank Lott in Flat. Frank was now the radio operator for Star Airlines and Pan American. He had taught himself to send and receive Morse Code giving the pilots weather and landing strip conditions, besides having a voice schedule with other miners.

I took over the job as welder and mechanic, helping with the cleanups and hooking up the pipeline to the trestle, after it was moved ahead with the dragline.

Our new D-8 came in July. Eugene and I walked the forty seven miles to Iditarod following the bald hilltops because the valleys were too swampy. We drove the tractor back, following the hilltops again.

The cleanups were good all summer, with lots of nuggets, but we were still a little in debt when freezeup came.

I made the six mile round trip every few days to the intake of our ditch either to let in more water or shut some off when it rained, which happened often. Hildur went with me now and then on these walks. One day as I went around a sharp bend, there, almost in front of me, was a big black bear with two cubs. She began slapping them into a tree, before coming to take care of me. I made a hasty retreat back to camp. After that I carried our old 30-40 Krag rifle, seeing lots of bears but none with cubs.

About the middle of August, 1937, an airplane flew low over our camp as if searching for something. Later that afternoon Oscar Winchell flew in with Ralph Savory, who had found the missing Star Airways pilot Dan Victor’s crashed plane. He had seen someone walking near it.

We said we could furnish seven men to go carry in the wounded, if any. With the eight they got from Flat we started out that evening on the twenty mile walk to the crash site. Half way there we stayed at an old log cabin until daylight. The next morning Winchell and Savory flew over, directing us to the spot, in heavy timber on a hillside.

They didn’t have radios on the planes yet so pilots had to take chances on getting through. The fog had closed in suddenly on Dan, so thickly he could not see. Being forced down, he shut off the engine and aimed between two trees, knocking off the wings but saving the plane cabin from being demolished.

We made stretchers out of spruce poles to carry out a woman passenger and a young man. Dan was able to walk but an old man was dead. They got him and the baggage with a dog team later that fall, and burned the plane so it would not be mistaken for some other downed plane.

Dan brought us a plane load of groceries some time later and landed well. But just before the plane stopped rolling a gusting crosswind turned him into a tailing pile, bending the propeller like a pretzel. Dan took it off, saying he would have to order a new one from Anchorage but an old man, Carl Thiel, a former toolmaker from Germany who was working for us, said he would straighten it.

Dan laughed. “You can if you want to, but I won’t take a chance to fly with it.”

Carl took it to our blacksmith shop and heated it, using our ancient bellows forge.

“You can’t heat it. It is aluminum!” Dan protested.

Carl told him to never mind, he knew what he was doing. “I only heat it to a certain point.”

Dan and I left. About three hours later Carl came to the mess house with the propeller looking as good as new. Dan decided to put it on just to see how badly it vibrated. We watched him start the engine.

“Can’t feel any vibration,” he shouted. “I’ll taxi up and down the field to see how it acts under a load.”

He went to the lower end of the field, coming back faster and faster. Then he took off, circled the air strip, dipped his wings, and headed toward Flat.

He told us later that the Anchorage mechanics put on a new propeller but he did not see anything wrong with the way the old one performed.

In 1945 Dan was flying a twin Beechcraft for the Morrison Knudsen Company during World War Two. A downdraft pulled him into a hillside near Nome, killing him and all on board. [editors note – This note came from Dan Victor’s son Nov-2004: “There are some errors however regarding my father’s death. He crashed and died near Moses Point in Norton Sound in November, 1942 while flying for the FAA”….”It was actually Hal Killam who was flying the twin Beechcraft for the Morrison Knudsen Company during World War Two. His plane iced up and he lost one engine before crashing and dying.”]

In the fall of 1937 Aina and I each sent Emmett Shaw some money for assessment work and to record our platinum claims again. This had to be done each year. Emmett wrote he was working for the Goodnews Bay Mining Company, which was owned by the Olson brothers, who used to mine in Flat; and that our claims were now recorded for another year. The next year we did not follow up on having our claims recorded because we felt the ground was probably poor. I saw Emmett years later in Fairbanks at the Nordale Hotel and he said our claims paid well to mine. But that’s the way it was if you did not do the assessment work ($100.00 worth) each year and record your claims they were open for anyone to stake.

When freezeup came in September, 1937, everyone except Hildur, Ray and I left to spend the winter in the states.

Tony Gularte and his wife, Eliza, and our family took a planeload of groceries to Moore Creek. Tony and Eliza lived in our big log cabin bunk house and we in the back room of the mess house. We had the nicest winter; shot a big bull moose for meat, trapped marten and played pinochle. We did a lot of skiing and snowshoeing, and enjoyed each others company.

On December twenty second we decided to go the forty six miles to Flat to attend the annual Christmas party and dance at the Moose Hall. Tony and I built a solid plank floor on the back end of the tractor sled, covering it with new galvanized sheet iron so the sticks couldn’t penetrate. We put a small tent over it with a sheet iron stove inside. Early the next morning in the dark we hooked the old 60 to the sled. The girls loaded groceries and a big cast iron kettle of moose meat mulligan (stew) they had made the day before. A small wooden box was Ray’s bed.

The snow was not too deep but we did have to break through some deep drifts. I was going in high gear down from Camelback summit, when the sled hit a stump and lurched. The girls had just put the mulligan kettle on the stove. It landed upside down on the sheet iron floor. So did little Ray’s box but he didn’t even wake up.

The girls quickly scooped up the mulligan, all but the juice, of course, and put in snow for liquid. I stopped to ask why it was taking so long to heat the mulligan. They told me to just keep going, it won’t be long.

Tony and I kept remarking how good it was, but not enough salt. The girls kept giggling and wouldn’t tell us what was so funny, until we were through.

Tony stood on the front of the sled the whole distance to keep branches from striking the tent. Reaching Flat late that night we went straight to our respective cabins. On Christmas Eve we enjoyed the children’s’ school program, dinner and an all night dance.

On Christmas day Oscar Winchell came so we got him to fly us back to the mine, leaving the 60 in Flat to be ready to start the trail breaking and freight haul in the spring.

In the latter part of May after all hauling was done, I set out on my skis to Flat to get the mail. Skiing long distances alone can be hazardous. The steel binding holders on my skis stuck out about a quarter of an inch on each side. Traveling fast down a steep hill twenty miles from camp, where the sled bunks had made a smooth hard trail, I tried to avoid a lump of frozen snow; but my right ski jammed into the sled runner rut, throwing me about twenty feet down the hill, my ankle sprained and my forehead cut. The ankle pained me, but at least I didn’t break a leg.

We started dumping gravel with the dragline into the dump box about the middle of June, ending with a very profitable 1938 mining season.

After freezeup Charlie and the crew went to Flat. Hildur, Ray, one of the men and I stayed at the mine, for I had overhauling and repairing to do on the bulldozers to ready them for freight hauling.

That winter we all went “outside” as the Alaskans say. Hildur, Ray and I visited Spencer, Phoenix, Los Angeles and Seattle; then back to Flat in March. Hildur and Ray stayed in Flat while Charlie and I flew to Moore Creek with two of our men to break the trail through. With the freight all hauled we came back to Flat for the load of groceries, including perishables that we wrapped in blankets covered by a big canvas, using a couple of coal oil lanterns to prevent freezing.

Hildur decided that she and Ray would ride to the mine on the grocery load. The weather was warm during the day by now. We stopped at the Bonanza relief cabin for the night. Hildur, Ray and I occupied the one and only bunk, while the men slept in sleeping bags on the dirt floor.

During the night Hildur was awakened by shrews–small, blind, mole-like animals–crawling through her hair. She spent the rest of the night guarding Ray and her hair from the animals, and listening to the men snore.

During the summer a diphtheria epidemic hit Flat. A man and a child died. Flat was quarantined; no one was to come in or leave. Cecil Barlow, an old man living on lower Moore Creek, happened to be in Flat. Ignoring the quarantine he walked home, and came to visit us. Very soon little Ray began complaining that he had a stick in his throat. A plane didn’t come until several days later. Hildur took him to Fairbanks. We were relieved to hear it was not diphtheria.

During the summer we had a rainy spell that lasted for eighteen days. It was so foggy that a plane could not get through with our weekly fresh meat. We searched the area every day for a moose but no luck.

One evening after work we saw a big black bear up on the hillside opposite camp, across Moore Creek. I took our 30-40 Krag rifle over to the creek and shot the bear from there. He fell and we presumed I had gotten him. Charlie Uotila and Walfred Hillman crossed the creek and began climbing the almost vertical bank to look for him. About half-way up the bank they sat down to rest.

Right below them, standing in the creek in shallow water, was a big bull moose. Walfred had often told us what a good shot he was, for he had hunted deer in Minnesota, so Charlie gave him the gun with the only two bullets we had in camp. He took careful aim and fired. The moose just shook his head.

“Give me the gun, quick,” whispered Charlie.

Walfred refused, saying, “I aimed too high!”

He fired the last bullet The moose staggered’ fell and lay kicking in the shallow water while they sat wondering how to get him out. It was too swampy for a tractor. Suddenly the moose got up and slowly walked away. All they could do was watch. The bear was gone too.

In the fall after freezeup Charlie and the crew waited for a Star Airways plane to come take them to Flat. Hildur, Ray and I stayed behind again so I could repair the tractors.

A young pilot named Dunkle came with a Waco biplane and asked to fly the crew in. He had just gotten his commercial pilot’s license and was starting his own business. He took three of the men and brought back a heavy load of tractor parts. He touched down too far up the field and tried to groundloop when he came to the end of the strip. The left landing gear buckled, breaking the lower wing, and the plane nosed over, bending the propeller.

The next morning, Oscar Winchell brought the rest of our tractor parts and took Dunkle and the rest of the crew to Flat. Young Dunkle came back with an Anchorage friend in another Waco, loaded with parts to fix his own plane. The friend undershot the runway and wrecked the Waco. The two men spent most of the winter at Moore Creek repairing the two planes.

A man named Joe Howard worked on the Alaska railroad when it was being built. He was injured, lived in Flat on disability payments, then went to work for the Alaska Road Commission. Someone reported that he was working, so his disability payments stopped. He was so angry at people in general, that he moved out to the hills near Moore Creek, making his living trapping. He came to Flat only twice a year after flour, sugar, etc. Once he didn’t show up for a long time, so Peggy Lott, who was now the U.S. Commissioner, sent two men to look for him. They had trouble finding his living quarters–a cave he had dug into a hillside. The place was a filthy mess with dog dung all over the dirt floor of the cave, they said.

Later he moved, building a small log cabin somewhere south of our freight hauling trail. We sometimes saw his snowshoe tracks and met him a few times.

In the spring of 1941 at 3:30 one morning, as we approached our half-way cabin with the tractors and freight, he came out in his long underwear to pull his sled out of our way. I told him that we did not want him living in our cabin.

“But,” he protested, “my cabin is so full of gas that was dropped from that black airplane again yesterday.”

We tried to be friendly, asking him to spend the rest of the night, to go back to his cabin after daylight.

But he left anyway, saying, “I am sure the gas is all out by now because I left the door wide open.”

Two days later we got back to the cabin. His sled was there and inside was his pack sack and a bundle of beaver skins but no Joe.

We noticed a small note on the table. It said, “Elmer, I don’t know what is the matter with me. The doctor seems to know anything and everything. ”

We looked around outside but saw no sign of him.

In Flat I reported this to the U.S. Commissioner, who sent Joe and Jul Stuver, former Montana cowboys, to look for him. Joe and Jul were at our halfway cabin when we got there, complaining that they couldn’t find Howard’s cabin. I knew about where it was for I had seen smoke from his chimney early one morning.

Jul and I put on snowshoes and located it about half a mile above our trail in heavy timber.

It was getting dark when we approached from the rear, with Jul and his cocked pistol in the lead. Peeking around the front corner, we saw the door slightly ajar.

Jul shouted, “Joe Howard! Are you in there?” No answer, so he gave the door a mighty kick.

Old Joe had put a pole from the floor sloping up against the wall next to his bunk, laid his head on the pole and had blown the top of his head off with his high powered rifle. He was taken to Flat with his dogsled and buried.

Gus left John Ogriz to run their Slate Creek mine, and he and Aina moved to Ophir, where we went into partnership with Eric Hard to mine on Ophir Creek.

Our new steel boxes were at Slate Creek so we hauled them along with five hundred barrels of fuel oil and gasoline each’ abandoning the trestle method.

We moved our camp about three quarters of a mile down the creek to start mining the creek flats, which averaged only about fifteen feet to bed rock.

We all had fun with little Ray. One evening as he and I headed for the sauna I bragged that I could take a bath and beat him to the house. We both started repeating, “E-e-e-easy beatsy!” while we hurriedly splashed a little water on ourselves, all the while repeating, “E-e-easy beatsy.” I let Ray beat me by a few seconds but when we got to the cabin, Hildur laid down the law and made us both go back to take a bath.

I made him a raft by welding two oil drums together end to end with a wide board on top to sit on. He enjoyed paddling around on it in a small pond by the mess house. One time he asked me to try it. It looked so easy that I did, while he and Hildur watched. I went about two feet when the thing flipped upside down. Ray laughed so hard, to see me standing in four feet of water with my clothes on, that he flopped on the bank.

My brother Leonard made Ray little wooden boxes and set them in a small stream on a slope in front of the mess house. He put in a small pipeline with a piece of garden hose to use for washing gravel into the boxes. The men thought they would have some fun so they buried a few brass drippings from the shop in the gravel in the boxes. They were sure Ray would be really excited…so after supper one evening they told him its about time he had a cleanup. They all watched while he took out the riffles and started washing out the gravel. When he saw the nuggets he picked one up and threw it on the ground saying, “Oh, heck, brass!”

At four thirty one afternoon I sent Charlie Ropponen about a mile up to our ditch to shut off some water. At eight o’clock he still had not returned. Cowboy Joe Stuver, Charlie Uotila and I went to see what happened. Joe had his rifle and I had ours. As we rounded a sharp bend of the ditch Ropponen came running. He said a black bear chased him up a tree and tried to climb the tree every few minutes. He finally disappeared into the willows allowing Charlie to escape.

At the waste gate of the ditch there was no bear, but about a quarter of a mile away we spotted him climbing a bank. Joe whistled, the bear turned and stood on his hind legs, then started coming toward us. We saw the willows shaking. Charlie Uotila and I backtracked a little but Joe stood firm. Soon he shot and yelled “I got him!”

Charlie and I didn’t see any bear so Joe took off his clothes and dived into the six foot deep pool in the ditch, coming up with the bear. We left him on the bank and the next day we saw where some animal had dragged him away. Might have been a wolverine.

Another time the same man went grayling fishing accompanied by Ray’s little dog. In going through the willows he saw a cow moose with a calf. The dog ran barking to the moose. The moose chased the dog, the dog ran and hid behind Charlie, who beat the dog with a stick. The dog ran yelping through the willows with the moose in pursuit. Charlie came running home and the dog soon followed.

Our camp now consisted of a new large cookhouse and cook’s room with a grocery storage building next to it, two large bunk houses, Charlie’s cabin, Eugene’s radio house, a sauna, tractor parts warehouse, blacksmith shop and a tractor repair shop with a pit in the floor for working under the tractors. Hildur and I lived in an old log cabin that had been there. 1940 was again a very profitable year.